(P.168)

As you work through Project 3, keep your eyes open for textiles in your everyday

life as well as in museums and galleries. You might find them in an office building, hospital or

public library, for example, or on public transport. Don’t just look at textile pieces on walls; think

about their more ‘utilitarian’ uses too , such as canopies, coverings, etc. If you can, find out who

made each piece and how it came to be sited there. Take a photo (e.g. on your mobile) and

make some notes.

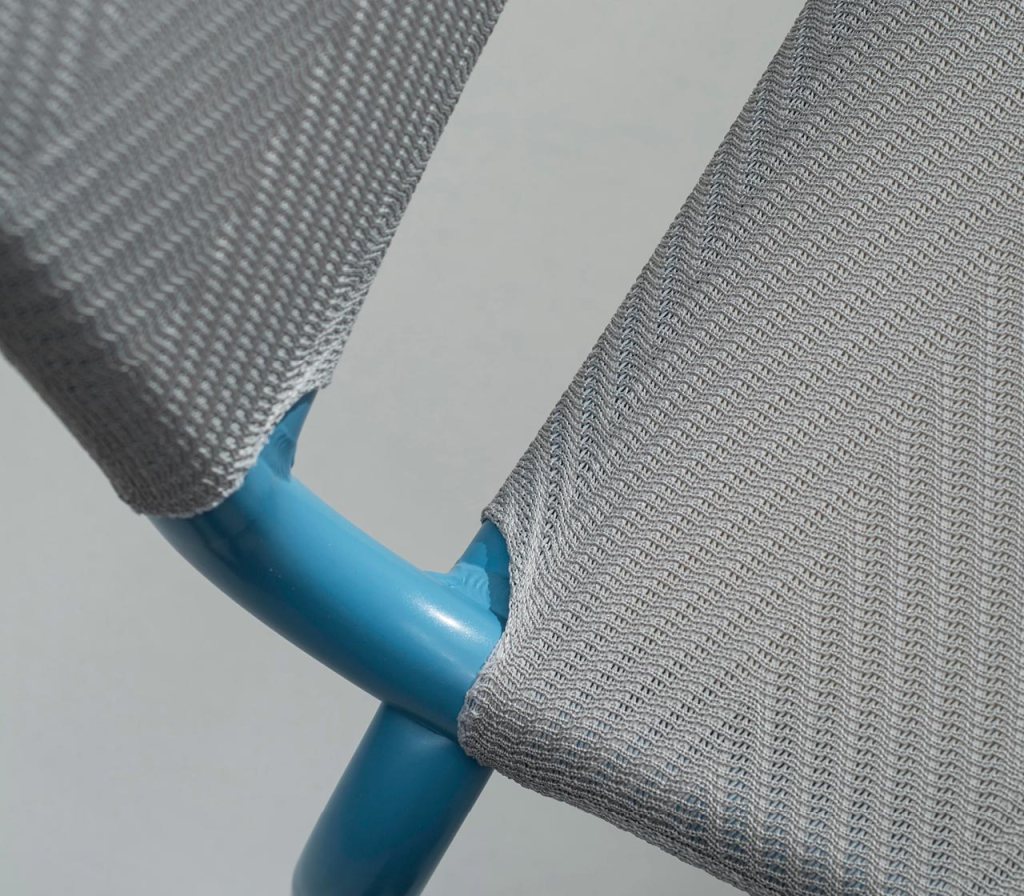

Below are some textile applications developed from companies I’ve worked with.

Benefits with knitting:

- Zero or almost no waste

- Fully shaped to user requirement

- individual design

- customized solutions

- minimum material use

- No stitches or additional processes necessary

Why Textiles?

Textiles are an ideal medium for interaction with the human body.

While many technological advancements necessitate radical change in behavior to be widely adopted, textiles have the benefit of being familiar to all people across society, inconspicuously integrated into our daily lives, and pervasive across all environments.

TEXTILES COVER ALMOST

100%

OF THE HUMAN BODY

Allowing for access to a range of bio-signals

and interaction through numerous form factors

TEXTILES ARE ADOPTED BY

100%

OF PEOPLE IN SOCIETY

Enabling adoption of technology regardless of life stage,

physical ability, or mental ability

TEXTILES ARE PRESENT IN

100%

OF OUR DAILY LIVES

Providing a continuous connection between the human body and the digital world.

To some cultures, textiles are woven into their history; they are an integral part of their being

and identity.

Refer to ‘Room Six: Territories’ Pages 146 & 147.

Investigate ‘Gers’ and other such textile based shelters/homes such as Wigwams,

Tipis and Tents.

Don’t be tempted to skip this exercise; you’ll need your research findings when you come to

Assignment Five. Turn to the assignment brief now so that you can start planning.

A traditional yurt (from the Turkic languages) or ger (Mongolian) is a portable, round tent covered with skins or felt and used as a dwelling by several distinct nomadic groups in the steppes of Central Asia. The structure consists of an angled assembly or latticework of wood or bamboo for walls, a door frame, ribs (poles, rafters), and a wheel (crown, compression ring) possibly steam-bent. The roof structure is often self-supporting, but large yurts may have interior posts supporting the crown. The top of the wall of self-supporting yurts is prevented from spreading by means of a tension band which opposes the force of the roof ribs. Modern yurts may be permanently built on a wooden platform; they may use modern materials such as steam-bent wooden framing or metal framing, canvas or tarpaulin, plexiglass dome, wire rope, or radiant insulation.

Wigwams (or wetus) are Native American houses used by Algonquian Indians in the woodland regions. Wigwam is the word for “house” in the Abenaki tribe, and wetu is the word for “house” in the Wampanoag tribe. Sometimes they are also known as birch bark houses. Wigwams are small houses, usually 8-10 feet tall. Wigwams are made of wooden frames which are covered with woven mats and sheets of birchbark. The frame can be shaped like a dome, like a cone, or like a rectangle with an arched roof. Once the birch bark is in place, ropes or strips of wood are wrapped around the wigwam to hold the bark in place.

A tipi /ˈtiːpiː/, often called a lodge in English, is a conical tent, historically made of animal hides or pelts, and in more recent generations of canvas, stretched on a framework of wooden poles. The word is Siouan, and in use in Dakhótiyapi,[1] Lakȟótiyapi,[2] and as a loanword in US and Canadian English, where it is sometimes spelled phonetically as teepee[3] and tepee (also pronounced TEE-pee).

Historically, the tipi has been used by some Indigenous peoples of the Plains in the Great Plains and Canadian Prairies of North America, notably the seven tribes of the Sioux, as well as among the Iowa people, the Otoe and Pawnee, and among the Blackfeet, Crow, Assiniboines, Arapaho, and Plains Cree.[4] They are also used west of the Rocky Mountains by Indigenous peoples of the Plateau such as the Yakama and the Cayuse. They are still in use in many of these communities, though now primarily for ceremonial purposes rather than daily living. Modern tipis usually have a canvas covering.[5]

Non-Native people have often stereotypically and incorrectly assumed all Native Americans in the United States and Indigenous peoples in Canada live in tipis,[6] which is incorrect, as many Native American cultures and civilizations and First Nations from other regions have used other types of dwellings (pueblos, wigwams, hogans, chickees, and longhouses).[5]

Four Kiowa tipis (1904) with designs. From top left to right: design featuring bison herd and pipe-smoking deer, porcupine design, design featuring arms and legs with pipes and lizard, and design featuring water monsters

CiteShareFeedback

By The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica Edit History

tent, portable shelter, consisting of a rigid framework covered by some flexible substance. Tents are used for a wide variety of purposes, including recreation, exploration, military encampment, and public gatherings such as circuses, religious services, theatrical performances, and exhibitions of plants or livestock. Tents have also been the dwelling places of most of the nomadic peoples of the world, from ancient civilizations such as the Assyrian to the 20th-century Bedouins of North Africa and the Middle East. American Indians developed two types of tent, the conical tepee and the arched wickiup, the latter constructed of thin branches or poles covered with bark or animal hides.

The simplest form of tent is an extremely portable type carried by individual soldiers in the field. When erected, it consists of a low pyramid, formed by a short, diagonally set pole at either end supporting two lengths of cloth joined together at the top and pegged into the ground at the bottom. This is a primitive form of the popular pyramidal A-shaped tent. A long-common tent, the conical bell tent, has a single large vertical pole at its centre and is circular at ground level. The tepee (q.v.) is a variant of this design. Other kinds of tent include the wall tent, an A-shaped tent raised to accommodate straight, vertical walls beneath the slope of the pyramid; the Baker tent, which is a rectangular fabric lean-to with an open front protected by a projecting horizontal flap; the umbrella tent, which was originally made with internal supporting arms like an umbrella but which later became widely popular with external framing of hollow aluminum; and the cabin tent, resembling a wall tent with walls four to six feet high. Special tent designs include mountain tents, which are designed compactly for use in conditions of extreme cold and heavy snow, and back-packing tents, which use extremely lightweight synthetic fabrics and lightweight metal poles. “Pop” tents are designed with spring-loaded frames that erect the tent automatically when released; these are usually hemispheric in shape.

Bedouin tents:

Indian wedding tents