Research point (P. 170)

Go online and read more about the Sackler Gallery extension.

Located just across the river from the main gallery building in London’s Kensington Gardens, the Serpentine Sackler Gallery occupies a 200-year-old former gunpowder store. Zaha Hadid Architects renovated the old brick building to create new gallery spaces, then added a curving cafe and events space that extends from one side.

The new tensile structure is built from a glass-fibre textile, forming a free-flowing white canopy that appears to grow organically from the original brickwork of the single-storey gallery building.

It stretches down to meet the ground at three points around the perimeter and is outlined by a frameless glass wall that curves around the inside.

Five tapered steel columns support the roof and frame oval skylights, while built-in furniture echoes the shapes of the structure.

“The extension has been designed to to complement the calm and solid classical building with a light, transparent, dynamic and distinctly contemporary space of the twenty-first century,” explain the architects. “The synthesis of old and new is thus a synthesis of contrasts.”

For the original building, the architects added a new roof that sits between the original facade and the outer enclosure walls, creating a pair of rectangular galleries in the old gunpowder stores and a perimeter exhibition space in the former courtyards.

A series of skylights allow the space to be naturally lit, but feature retractable blinds to darken it when necessary.

Can you find any

more examples of architectural uses of textiles?

The term ‘architectural fabrics’ generally refers to structural fabrics used to form tensile surfaces, such as canopies, roofs and other forms of shelter. Architectural fabrics are generally held in position by tension forces imposed by a structural framework, a cabling system, internal air pressure or a combination.

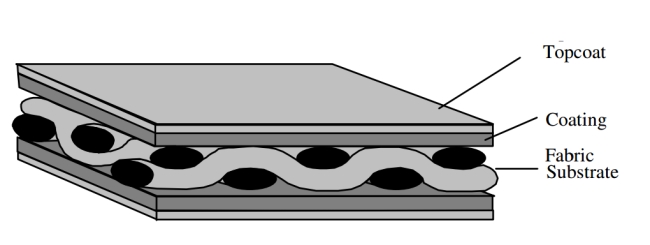

Typically, the membrane is formed by a fabric, consisting of a woven base cloth, coated on both sides with an impermeable polymer, and sometimes a durable topcoat, however a wide range of variations are available, ranging from open weave fabrics, to transparent foils.

Architectural fabrics are generally very thin, approximately 1mm thick and have very little compressive strength, but very high tensile strength.

The typical tensile strengths of architectural fabrics are set out below:

- Type 1: 3,000 N/5cm.

- Type 2: 4,000 N/5cm.

- Type 3: 5,550 N/5cm.

- Type 4: 7,000 N/5cm.

- Type 5: 9,000 N/5cm.

Cotton

Cotton was one of the earliest materials used as an architectural fabric, and is still in use today. It is relatively inexpensive and is available in a wide range of colours, but it has a lower tensile strength than some more modern materials, and is prone to staining and shrinkage. It has a relatively short life expectancy, but can flex repeatedly without cracking, and so tends to be used for small-scale, temporary structures.

PVC polyester

PVC coated polyester is the most commonly used architectural fabric. It is relatively inexpensive, has reasonable structural strength and translucency, can be joined relatively easily at seams by welding, and has an reasonable life expectancy.

Structurally, PVC polyester can last in excess of 20 years, however, it becomes more difficult to clean as the plasticisers used to make the PVC flexible leach to the surface, and so it is generally expected to last 10 to 15 years.

It is often manufactured with a topcoat such as PVDF (polyvinylidene fluoride), which improves its cleanability, but generally reduces its weldability, and so must be removed in the region of welded seams. Topcoats can increase the lifespan of PVC polyester to 15 to 20 years.

NB: PVC has been criticised for its environmental performance, with claims that the chemicals used to plasticise the PVC can be harmful to the environment. However, alternatives such as polyolefin coated polyester have struggled with fire resistance issues, and fire retardants added to the coating have resulted in reduced adhesion at seams.

PVC nylon

The less common PVC nylon is similar to, but has a higher elasticity than PVC polyester, and so has been used for the fabrication of air-supported and air-inflated structures.

PTFE glass

PTFE (polytetrafluoroethylene or ‘Teflon’) coated glass can be stronger than PVC polyester, and is longer lasting, with a life in excess of 30 years. However, it is more expensive and is relatively inelastic, and so requires more accurate patterning.

PTFE is a cream colour when new, but bleaches white in sunlight and is generally self cleaning if regularly exposed to sunlight.

Silicone glass

Whereas PTFE is translucent, silicone is transparent, and silicone coated glass has an anticipated life of up to 50 years. It has good fire resistance and low toxicity, but is not weldable, and so the seaming process requires an adhesive, and silicone can be difficult to keep clean.

EFTE foil

Ethylene tetrafluoroethylene (ETFE) is a relatively transparent foil that can be used as a lightweight alternative to glass. It can be used as a single layer, or in multiple layers of up to 5 layers, inflated to form large cushions.

Embrace Building Wraps-Kavalan Sunlight PVC-free.

No artists have used textiles on the scale and with the same impact as Christo and JeanneClaude. Well-known for their wrapping of the Reichstag in Berlin

n 1976, Christo travelled to Berlin for the first time. It proved to be an extremely significant visit. Even 19 years after his escape to the West, he had good reason to fear that he might be kidnapped by Communist spies and taken back to Bulgaria for punishment. Nevertheless, he was drawn to the no-man’s-land between East and West Berlin, and particularly to its most prominent landmark. The Reichstag, an old German parliament building, had stood almost completely disused since it was set on fire in 1933, an event that prompted the Nazis to more or less suspend the country’s constitution.

Christo and Jeanne-Claude spent the best part of the next 20 years petitioning for permission to create a work on the site, a concept not dissimilar from their Pont Neuf project: it would see a huge building freighted with historical significance draped in fabric, symbolically hiding the past and creating a blank slate for modern German identity. The idea proved controversial even after the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989, but in 1994, Christo and Jeanne-Claude finally received permission for this most ambitious project. Once completed the following year, Wrapped Reichstag captured the attention of the world, and became a symbol of the united Germany. It’s no exaggeration to say that this extraordinary achievement marked the rebirth of Berlin as a world city.

and the Pont Neuf in Paris,

Spanning the Seine River and crossing the western tip of the Ile de la Cité, Pont Neuf is Paris’s oldest bridge and one of its most historically important monuments. “I wanted to transform it, to turn it from an architectural object, an object of inspiration for artists, to an art object, period,” Christo told Le Figaro in 1985. To do this, he planned to wrap the entire structure in plastic fabric, creating a bizarre and distinctly modern illusion in the most ancient part of Paris.

Beautifully simple though the idea was, its execution would be anything but. Christo and Jeanne-Claude had worked with historical buildings before, but had never approached one that was both an icon of a major city and a busy public thoroughfare. This did not deter them, and in 1975, they began raising funds for their first big project in the French capital since 1962. This time, however, it was clear they would need permission from a dizzying number of different administrative bodies. After nearly a decade of negotiations, the project was completed in September 1985 to a sensational response, making Christo (if not Jeanne-Claude) one of the most famous artists in the world.

Surrounded Islands sees textiles used on an extremely large scale to both define and cover

aspects of the natural environment, in this case two islands.

See: http://www.christojeanneclaude.net/projects/surrounded-islands#.UtFAHrRDf6A [accessed

08/12/18]

Christo Javacheff and Jeanne-Claude Denat met in 1958, when the former was commissioned to paint a portrait of the latter’s mother. The pair had been born on the same day in 1935—he in Bulgaria; she in Morocco, where her father served as an officer in the French army. Nevertheless, their union was an unlikely one; Jeanne-Claude came from a respectable family and was already engaged to be married. Christo, on the other hand, was a stateless art school dropout who had fled his native country—then a repressive Soviet client state—by stowing away on a goods train. Yet within a year of their meeting, Jeanne-Claude was pregnant with their first child.

Together, they began to envisage conceptual projects using whatever materials they could afford. Oil barrels were a particular focus of their early work: On the one hand, they were cheap and easy to stack to formally imposing effect; on the other, their normal function alluded to the West’s dependency on oil, opening up a frame of reference that encompassed politics, economics, and environmental matters. On the night of June 27, 1962, Jeanne-Claude and Christo began assembling their first major outdoor project: an obstacle on a narrow street in Paris’s Latin Quarter created from 89 oil drums turned onto their sides. It stretched from one end of the street to the other, completely blocking the thoroughfare to pedestrian and vehicle traffic for the eight hours it stood in place.

It caused a commotion, and the artists—who had failed to get permission from the police prefect—almost got themselves arrested. Yet for all that it angered local motorists and outraged officials, TheIron Curtain captured Paris’s imagination. Unsurprisingly, given its title and Christo’s dramatic past, some read it as a comment on the Berlin Wall, which had risen overnight in the East German capital less than a year before. The work stood as a powerful political statement—one that also presaged the barricades that would be constructed by rioting students in the area six years later.

The next 15 years saw Christo and Jeanne-Claude go global. In 1964, they moved to New York, eventually acquiring American citizenship. From their new base, they developed their own commercial enterprise: In order to maintain artistic independence, they sold preparatory drawings and models to finance larger projects. (Christo still self-funds everything he does this way, accepting no subsidies or official partnerships.)

This new model of working allowed the artists to take on their first truly monumental projects. In 1980, they embarked on their most visible adventure yet: a proposal to surround 11 uninhabited islands in Biscayne Bay, Florida, with pink plastic “skirts” woven to fit the contours of the land. As with all of their work of this period, the project was credited to Christo alone, but he freely admits that the driving force behind the concept and its execution was Jeanne-Claude. Though this seems odd (if not indefensible), there was a rationale to it: Both believed that people would be confused by the idea of two artists working together as a single force, and in the male-dominated art world of the time, it seemed a better bet to credit Christo as the author of the work. It was only in 1994 that the billing was changed to represent Jeanne-Claude’s contributions.

After nearly three years of negotiating with both public and private bodies, the Surrounded Islands finally came into being in 1983. It involved some 6.5 million square feet of polypropylene fabric, and could be seen from miles down the coast. Though it was in place for just two weeks, the project attracted thousands of visitors and proved to be a landmark in Florida’s cultural history. As a testament to its importance, the Pérez Art Museum Miami will be showing an exhibition dedicated to Surrounded Islands from October 2018 through February 2019.

Surrounded Islands sees textiles used on an extremely large scale to both define and cover

aspects of the natural environment, in this case two islands.

Note down your thoughts on this work in your learning log. Do you agree with our analysis

above?

Even though I really admire the effort and the I can see the inspiration behind the work, I totally disagree with the artwork perception. It looks to me more like a project, an exercise, than a work of art. The scale is massive and the only way people could appreciate the whole work is through a photograph or being on a helicopter

I also believe art should bring beauty in our lives giving the extra spice that we need. Spice is used to enhance the senses and give bliss and eudaimonia in our experience. Too much of it is not good though: it ruins the balance. This kind of work reminds me of that; too much spice.

The Floating Piers. Lake Isleo. Italy 2014-2016.

Running Fence: 5.5 meters (18 feet) high, 39.4 kilometers (24.5 miles) long, extending east-west near Freeway 101, north of San Francisco, on the private properties of 59 ranchers, following the rolling hills and dropping down to the Pacific Ocean at Bodega Bay. The Running Fence was completed on September 10, 1976.

In their Wrapped Trees project, Christo and Jeanne-Claude use textiles as an effective means to

temporarily transform and define the trees. They state on their website that:

“The “wrapping” is NOT at all the common denominator of the works. What

is really the common denominator is the use of fabric, cloth, textile. Fragile,

sensuous and temporary materials which translate the temporary character of

the works of art.”

http://www.christojeanneclaude.net/common-errors [accessed 08/12/18]

Research point (P. 171)

Find out more about the Wrapped Trees project. As you’ll see, the wrapping both

hides and draws attention to the forms inside. Re-read the quote above and then look at the

work from the point of view of the textile rather than the trees. How does this affect your

experience of this piece of work?

In the examples that follow, we’ve left it to you to highlight the relevant terms to describe each

context.

Christo and Jeanne-Claude

Wrapped Trees, Fondation Beyeler and Berower Park, Riehen, Switzerland, 1997-98

. Wrapped Trees (1997–98) SOURCE: Alex Greenberger Senior Editor, ARTnews accessed: 2-12-22.

Amount of fabric used: 592,015 square feet

Like many wrappings by Christo and Jeanne-Claude, this one took a few failed attempts before it was actually executed. They first tried to wrap trees at the Saint Louis Art Museum in Missouri, and then along the Champs-Élysées in Paris. Both times, officials denied permission. But finally, the Fondation Beyeler in Switzerland said it was interested in realizing Wrapped Trees, and working with a large team that included project managers, fabric producers, tree pruners, climbers, and construction workers, the work finally came into being during the 1990s at the museum and the adjacent Berower Park. As usual for the duo, Christo and Jeanne-Claude funded its production through the sales of preparatory drawings and related photo-based artworks.

I wasn’t aware of the wrapped trees project. I when I saw it a word coming deep out of my lungs emerged: suffocation! I find this product even more audacious and selfish than the islands project. The trees are standing there being wrapped up with fabric unable to react or to show any kind of suffering. But, just imagine how life would be without any birds being able to rest and nest! It is literally like the tree is turning to a tile, a decorating pole, serving no purpose just feeding up the human ego. If that was the artist’s purpose, as provocateur to create such feelings then I’m their goal has been achieved.