Exercise 3: Changing Approach — From Idea to Image, and Image to Ethos

In this exercise, I challenged myself to invert my typical approach to creative practice. Historically, I begin with concepts rooted in personal experience, emotion, and linguistic expression. My work is often driven by words, memory, and metaphor—poetry first, visuals later. However, in response to this prompt, I embraced a visual-first process, one that let form guide the journey rather than ideas alone. I aimed to explore what happens when I allow the medium, visual language, and formal composition to lead me somewhere unexpected, before attempting to “explain” it in words.

This reversal opened up a whole new perspective on authorship, vulnerability, and intuition. I found myself working more intuitively, not knowing where the piece would lead me, and it was precisely in that not-knowing that something compelling began to take shape.

Initial Shift: Visuals Leading the Way

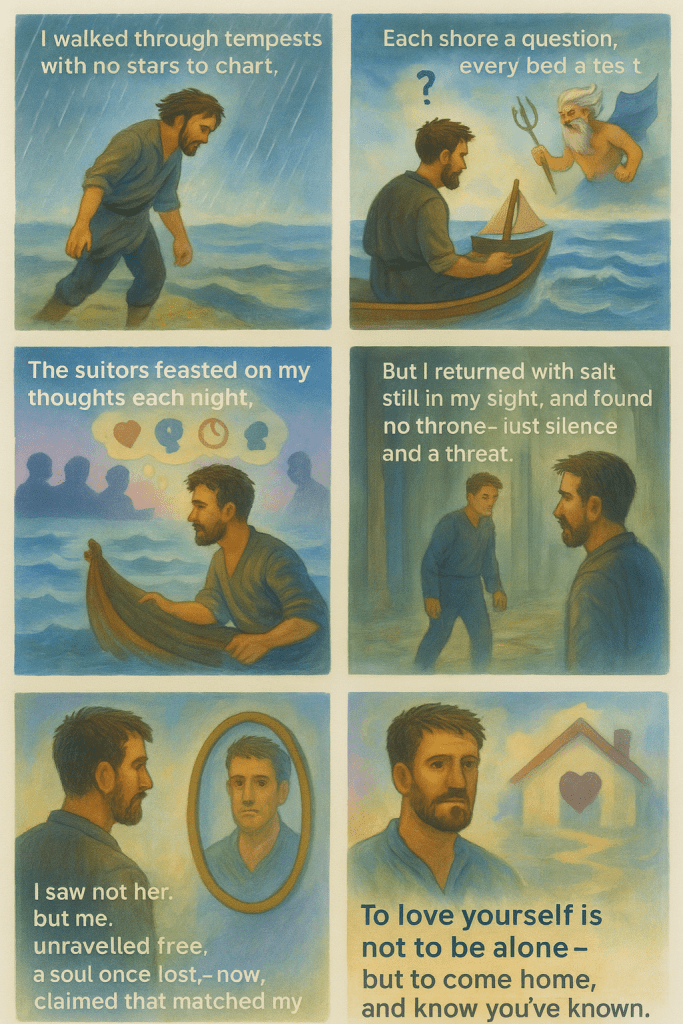

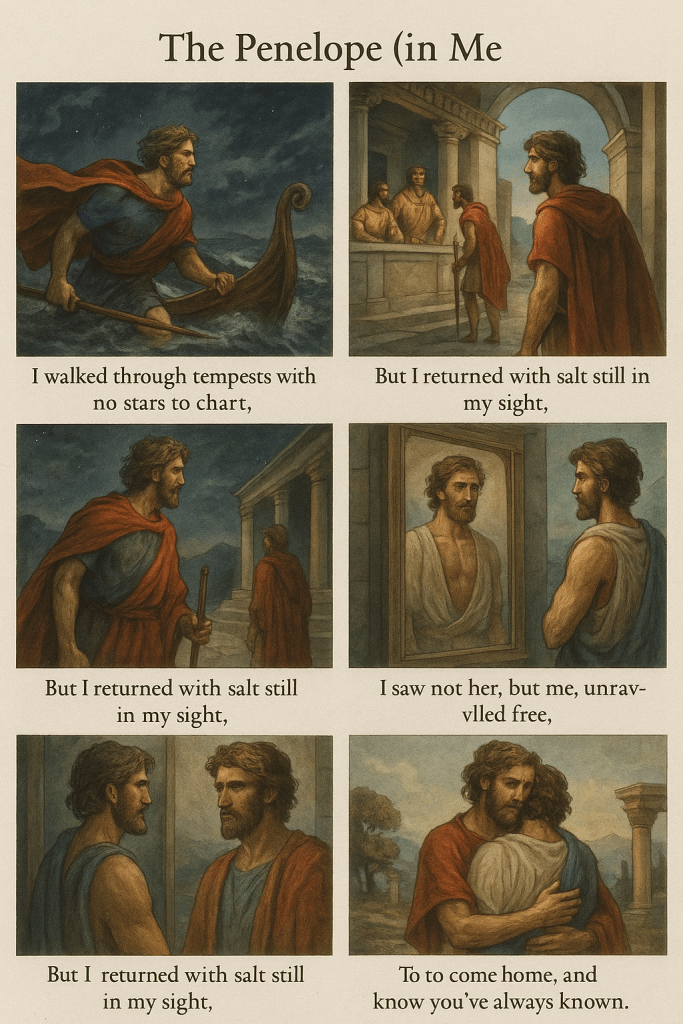

The first breakthrough came with the illustrated poetic sequence “The Penelope (in Me)”, which was initially a written poem about emotional exile and self-discovery. To push against my usual method, I recreated it as a visual narrative told through six sequential panels, where each stanza was represented through symbolic scenes. Using AI, I reimagined the visuals in three aesthetic styles: a monochrome, a more contemporary and internalised one, and the other drawn from mythical Greek visual traditions, referencing the neoclassical palette and symbolism of Odysseus’ return as portrayed in traditional Hellenic ceramics and frescoes (the last one came out with completely wrong wording but I kept it to signify the AI creation challenges).

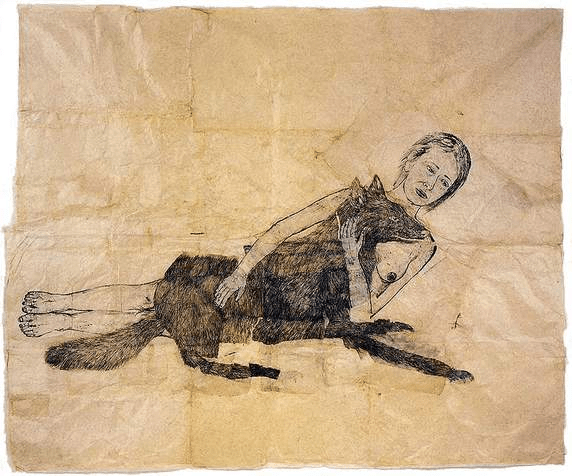

Inspired by the work of Kiki Smith, particularly her print series “Lying with the Wolf”

– I sought to explore the emotional vulnerability of the human figure in a way that balances both fragility and power. Smith’s ability to depict the body not as an object of perfection, but as a raw vessel of experience, resonated deeply with me. Her figures are often contorted, exposed, or entangled with animals and natural forms, suggesting a visceral connection to instinct, myth, and memory.

What struck me most was how she reclaims mythological and archetypal imagery, not to romanticise it, but to personalise it. In “Lying with the Wolf,” for instance, the female figure is not threatened by the wolf but lies peacefully beside it. This reversal of the predator/prey dynamic redefines vulnerability as a form of strength. That gave me the courage to tell my own symbolic story visually, through figures that feel unguarded, caught in quiet, often uneasy transitions.

In my work, I aimed to echo this emotional terrain: the moment between being lost and being found. Isolation and arrival became two emotional poles I wanted the viewer to feel oscillating between, sometimes within a single frame. The human form, often placed alone or in ambiguous relational tension with other figures or natural elements, becomes the map of that journey. There is no fixed narrative, just a continuous negotiation of space, self, and other, much like the internal myths we all carry within us.

By adopting a similar use of muted palettes, open spaces, and recurring symbolic motifs (in my stories, such as birds, bare trees, or fragments of landscape), I invite the viewer to project their own emotional narratives onto the figures, just as I have. Rather than illustrating a specific story, I want the work to feel like a myth in flux: shaped by memory, emotion, and transformation.

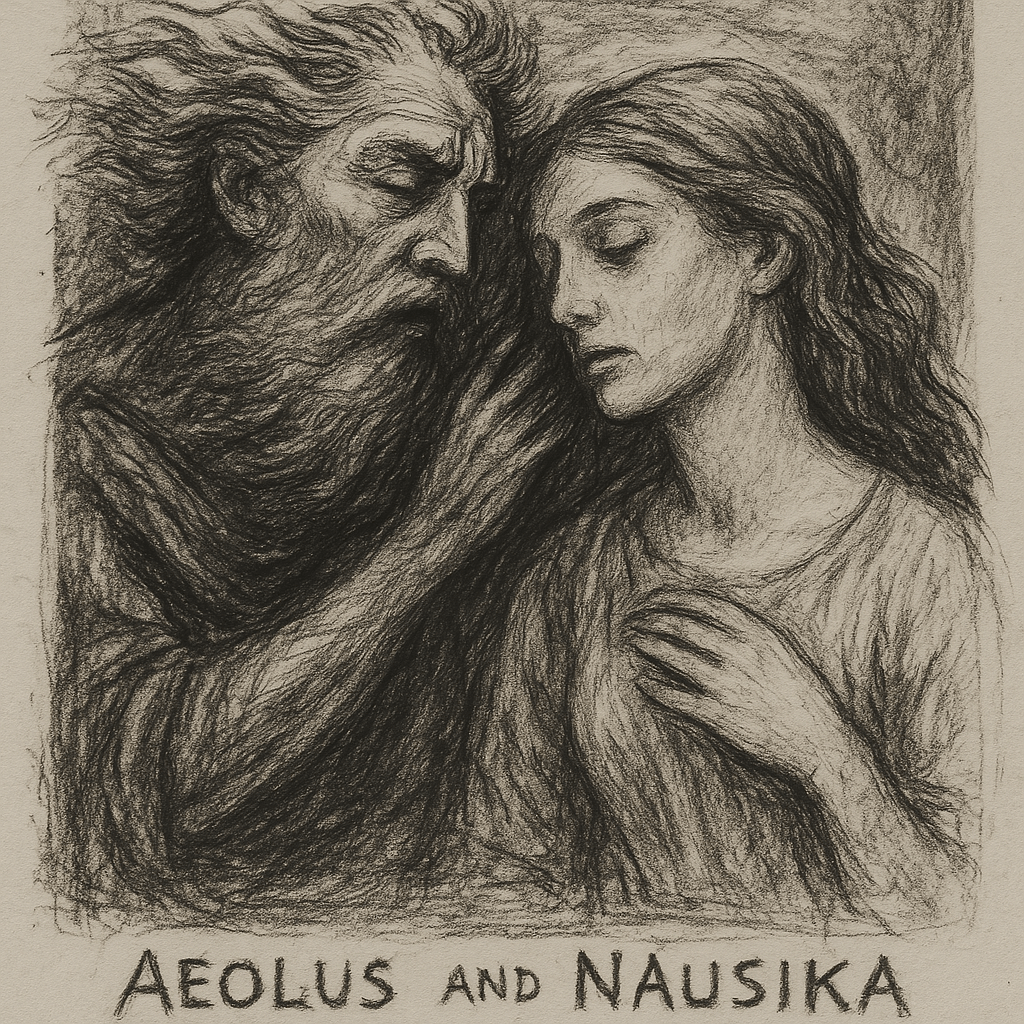

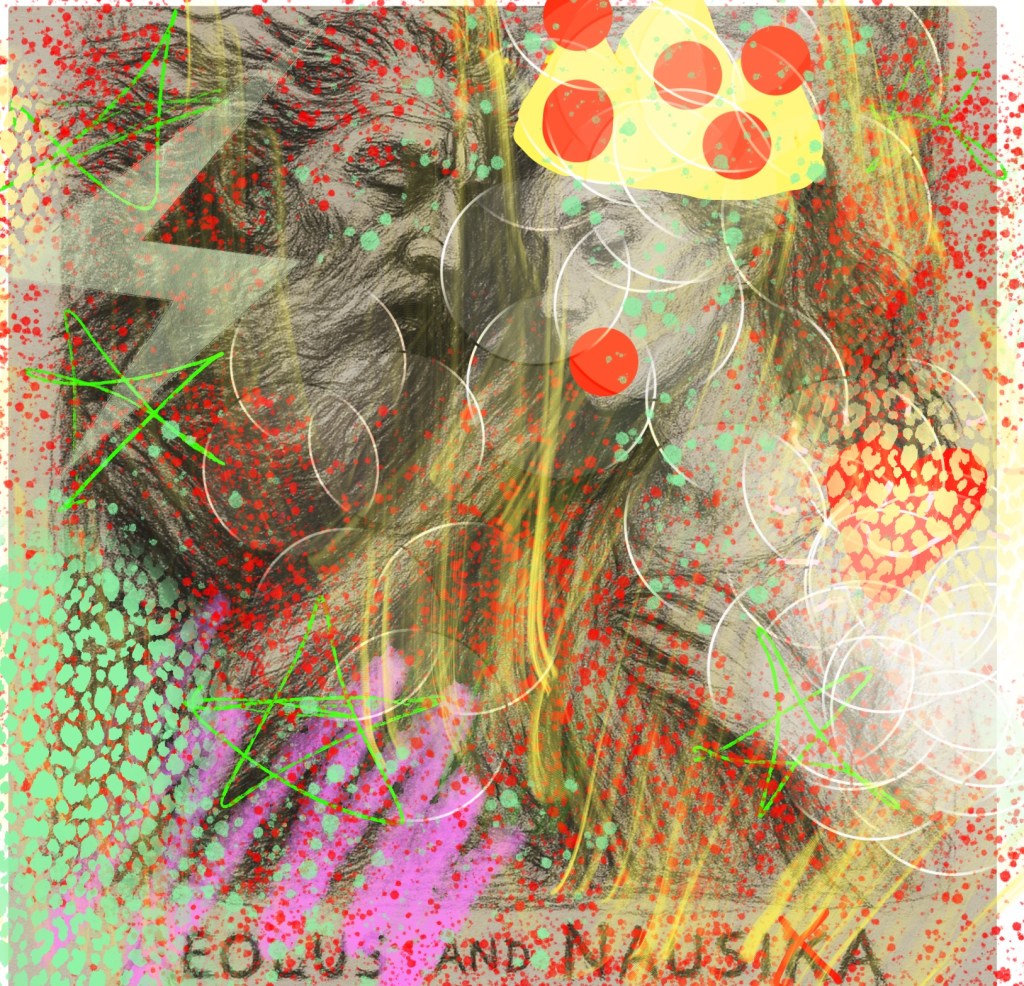

Material and Emotional Discovery: “Aeolus and Nausicaä”

Next came the visual accompaniment for “Aeolus and Nausicaä”, a poem that began with myth but ended in contemporary reflection. This piece took on a life of its own as I focused not just on narrative, but on atmosphere. I experimented with charcoal-like AI texturing and digital overlays to create a mood that was turbulent, soft, and filled with longing, similar in spirit to Anselm Kiefer’s “Des Malers Atelier”, where layered surfaces evoke memory, trauma, and mythical ambiguity.

Working with this duality (Aeolus as the storm-bringer; Nausicaä as the still point) gave me insight into the way myth can be visualised not as static allegory, but as emotional territory.

Again, I didn’t write and then draw—I allowed the drawing to inform how I revised and interpreted the written poem.

I have created two images: one raw and monochrome, and the other multicoloured and somewhat layered, inspired by Anselm Kiefer’s “Des Malers Atelier”. Nausicaä is the princess, and Aeolus is the wind bearer and the sea stirrer.

Then, using the Procreate App, I went back to the original monochrome picture and I created a multilayered coloured one , inspired by Basquiat: a great graffiti artist, in order to be more playful by giving to the original classical style one a modern and fresh view.

I was really happy with the outcome and the realisation that the possibilities of self expression between media are really endless.

Unexpected Outcome: The Bird Who Came From Afar

Perhaps the most spontaneous and illuminating part of the process was a short visual narrative titled “The Bird Who Came from Afar”. This was never part of my original plan, but emerged organically from my experimentation and experience. The piece began with a sequence of photos taken during my time in China. At the time, they felt like fragments: pieces without a story. But the act of revisiting them, arranging them, and giving them visual rhythm uncovered a story about belonging, flight, and transformation.

Pairing it with a stripped-back piano version of “November Rain” by Guns N’ Roses gave the piece emotional resonance, though finding the right musical tone was a difficult, almost obsessive task. I tried multiple versions before this one revealed the emotional truth of the images.

This work taught me that failure isn’t always dramatic: often it’s subtle. The failure here was the narrative’s initial invisibility. I didn’t see the story until I surrendered control, until I started arranging visuals without insisting on clarity. The struggle to not know allowed something real to appear.

Emotional Anchors: The Rare Seashell

An emotional touchstone in this entire process was the poem and illustration titled “The Rare Seashell”, inspired by the work of Nikos Kavvadias and Moniza Alvi, but also deeply personal. It was about recognising something beautiful (almost divine) but knowing you couldn’t keep it. I approached this piece visually before writing the final poem.

AI-generated, a single drawing of a man staring at the sea, empty-handed but full-hearted, guided the tone. This image embodied longing, restraint, and acceptance, and only after visualising this could I put it into words.

Much like Sophie Calle’s work “Take Care of Yourself”, where personal heartbreak becomes a conceptual visual project, “The Rare Seashell” translated an intimate emotion into a form others could enter. In this work, failure was not about rejection, but about accepting ephemerality: something I would have found difficult to explore had I begun with words alone.

The work originated from a break-up email Calle received from a lover. The final line of the email read:

“Take care of yourself.”

Rather than respond directly, Calle turned the letter into the material of her next artwork, inviting 107 women from different professions and backgrounds to interpret the email through the lens of their expertise.

The Structure of the Work:

Each woman, including lawyers, dancers, actresses, psychologists, editors, singers, and more, was asked to read, analyse, or perform a response to the break-up letter. These responses were presented as:

- Photographs

- Video recordings

- Written analyses

- Song lyrics

- Performances

- Marked-up texts

The work was first presented at the Venice Biennale in 2007 and filled an entire room with the various interpretations and perspectives.

Key Themes and Concepts:

1. Emotional Detachment through Multiplicity

By outsourcing the interpretation of the letter, Calle distances herself emotionally — transforming personal heartbreak into collaborative, analytical, and performative art.

2. The Female Gaze and Collective Response

Calle enlists only women, suggesting a collective female response to the experience of romantic rejection — one that is intellectually diverse, creative, and emotionally layered.

3. Language as Both Weapon and Material

The letter becomes a text to be dissected. It’s treated as a legal case, a dramatic monologue, a musical score, a psychological diagnosis — turning the intimate into the analytical.

4. Control, Healing, and Power

By taking ownership of the letter and reframing it through multiple voices, Calle reclaims agency over the narrative, turning heartbreak into artistic power.

Significance

“Take Care of Yourself” is often cited as one of Calle’s most significant works because it:

- Challenges ideas of authorship and intimacy

- Blurs the boundaries between life and art

- Invites questions about how women process emotion

- Shows how language and emotion can be externalised and objectified

Conclusion

Sophie Calle took a private moment of heartbreak and turned it into a public, multifaceted conversation about loss, self-care, interpretation, and power.

The simple phrase — “Take care of yourself” — becomes ironic, because that’s exactly what she does, by making art out of it.

Installation view of Sophie Calle’s “Take Care of Yourself” at the 2007 Venice Biennale (Photo: Florian Kleinefenn / Aia Productions; courtesy of Galerie Emmanuel Perrotin, Arndt & Partner, Gallery Paula Cooper)

Reflection

By reversing my creative process, I experienced a kind of freedom I had not known before. Normally, I write from emotion, then illustrate, using visual media. Here, by working from form first, I allowed images, composition, even myth, to shape what I would come to understand about my own emotional state.

The process gave me new respect for non-verbal knowledge, the kind of awareness that sits in the body, in silence, in colour and gesture. It made me realise that form isn’t the vessel for content: it can be the story itself. Most importantly, it reinforced that failure is not the opposite of success, but rather a necessary stage in the creative process: a helpful lesson.

This experiment will influence how I approach future work. I don’t intend to abandon idea-led practice, but I now recognise the power of visual intuition. Sometimes, the hand knows before the heart does. And that is a kind of wisdom worth trusting.