Research Task 1: What is ‘experimental’ poetry?

To me, ‘experimental’ poetry means stepping outside of fixed forms and traditional expectations of what poetry “should” be. Instead of following strict meter, rhyme, or structure, experimental poetry explores language in new ways: breaking lines unexpectedly, blending prose and verse, playing with visual layout, using fragments, or even incorporating other media like images, sound, or digital tools. At its heart, experimental poetry challenges conventions — both of form and of meaning — to open fresh ways of expressing experience.

Personally, I feel I sit between traditional and experimental writing. Much of my work is rooted in narrative and metaphor — for example, The Bird Who Came from Afar, where I use allegory and myth-like structure to reflect my own journeys. In that sense, I draw from traditional storytelling and lyric modes. But at the same time, I often experiment without naming it: I shift between poetry and diary, blur fact with metaphor, and allow irony or humour to disrupt romantic imagery. This kind of layering feels experimental to me, because it refuses to stay inside one box.

When I reflect on my own poems, I notice they are less about polished form and more about process — trying, failing, reshaping, and mixing voices. Sometimes I even write as though I am in dialogue with myself, or with the people from my life who appear in my metaphors. That feels experimental because it is not fixed; it is searching.

So, for me, being “experimental” is not about rejecting tradition entirely, but about allowing myself to play with language and structure, and to use poetry as a space where contradictions — romantic and ironic, personal and universal — can exist together.

Glossary

- Avant-garde poetry: Poetry that deliberately breaks away from established traditions, often experimental in form, language, and subject. It challenges norms and seeks to innovate, sometimes shocking or disorienting its audience. Examples: Dada, Surrealism, Language poets.

- Traditional poetry: Poetry that follows established conventions of form and structure, such as rhyme schemes, meter, and fixed stanza patterns (e.g., sonnets, ballads). It often values clarity, beauty, and continuity with earlier poetic traditions.

- Postmodern literature: A movement after WWII that questions absolute truths, often playful, fragmented, intertextual, ironic, or self-referential. Postmodern poetry might blur genres, include parody, or mix high and low culture.

- Confessional poetry: Emerged in the 1950s/60s (e.g., Sylvia Plath, Robert Lowell). It’s highly personal, drawing on the poet’s own private life, struggles, traumas, or intimate experiences.

- New Formalism / Neo-Formalism: A late-20th-century movement that revived interest in traditional forms and meter after decades of free verse dominance, often combining formal structure with contemporary themes.

- The Cambridge School: A loose group of avant-garde poets associated with Cambridge (UK) from the 1960s onwards, known for experimental, linguistically complex work (e.g., J.H. Prynne).

Research Task 2: Reflection

As I read about these categories, I see that my writing often sits in a liminal space between the traditional and the avant-garde. On one hand, I am drawn to confessional poetry — because so much of my work grows directly out of my lived experience: my travels, my family, my sense of isolation, or my encounters in China. Like confessional poets, I draw from memory, emotion, and honesty.

But at the same time, my approach is rarely “traditional.” I don’t follow strict meter or rhyme. Instead, I experiment with form: blending diary entries, poetic fragments, and metaphorical storytelling. In that sense, I lean toward the avant-garde — though not in the radical, language-stripped way of the Cambridge School or extreme postmodern fragmentation. Rather, I experiment with how personal narrative can be lifted into metaphor, sometimes romantic, sometimes ironic.

If I had to categorise my current work, I would say it is postmodern-confessional. Postmodern, because I am willing to blur genres (diary + poetry + image + memory + irony) and to question what is “real” or “fictional” in a poem. Confessional, because I can’t detach my poetry from my own emotional truth.

I don’t think I belong to the “traditional” side, nor do I fully embrace the avant-garde extremes. I am somewhere in between, experimenting with voice and form while staying anchored in lived experience.

Here are some engaging examples of visual and concrete poetry:

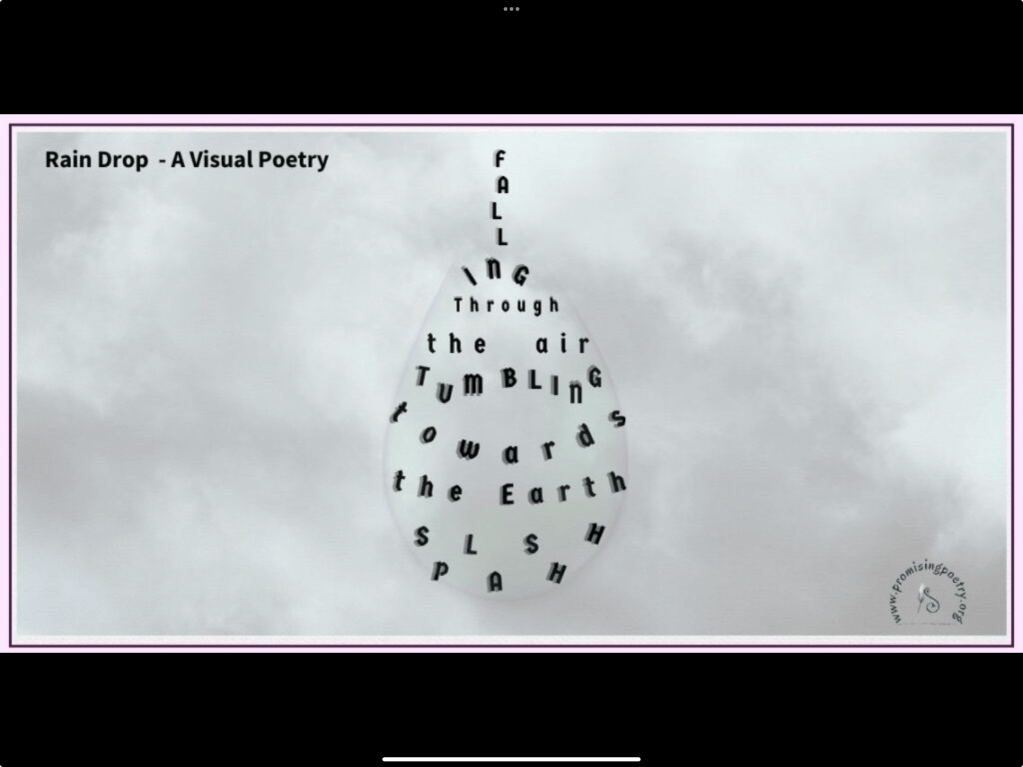

1. Falling Words Visual Poem – Words cascade in the shape of a droplet: “Falling through the air tumbling towards the earth splash.” The layout echoes the motion it describes.

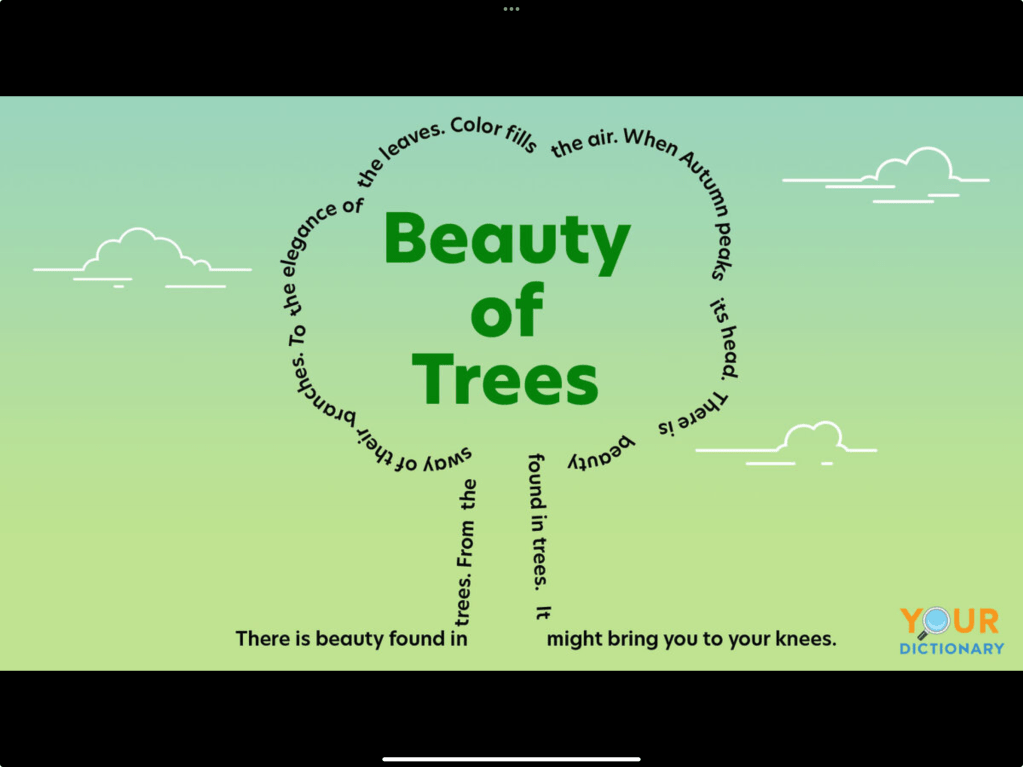

2. Tree-Form Concrete Poem – Words arrange into a tree-like shape, both visually and textually capturing growth or rootedness.

3. “Beauty of Trees” Concrete Poem – A solid tree outline built from poetic lines about autumn and nature’s grace.

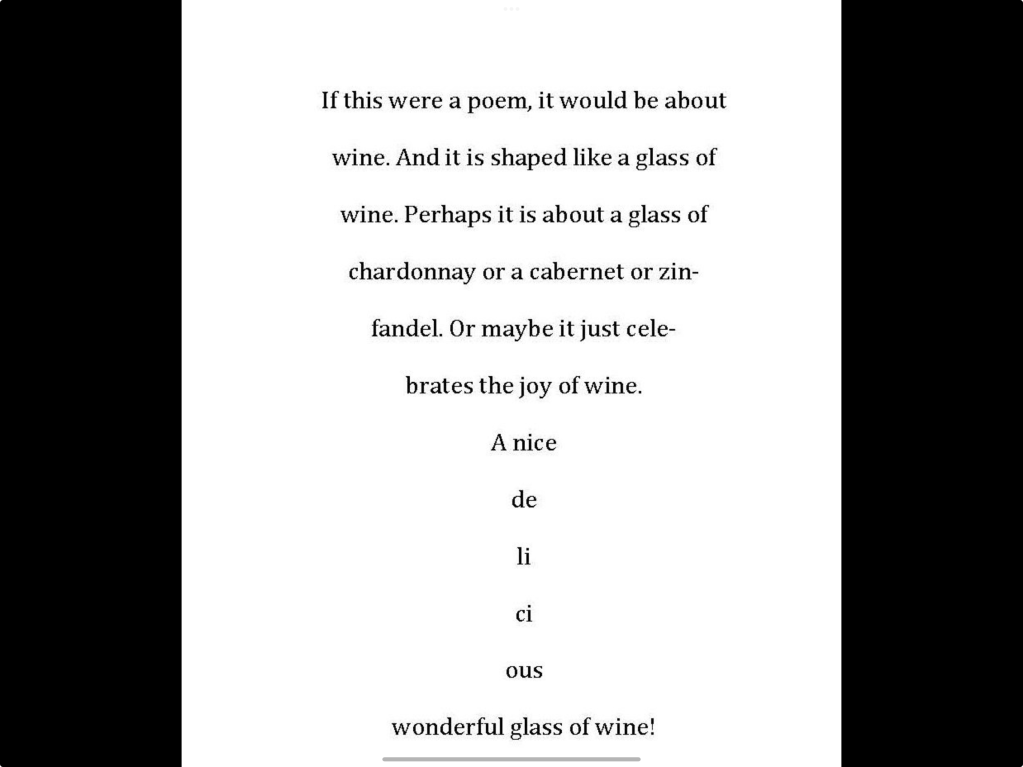

4. Wine Glass Concrete Poem – A poem shaped like a wine glass, where layout and content work together to evoke a sensory experience.

⸻

Reflection: Visual vs. Concrete Poetry

Visual and concrete poetry transform words into visual objects. According to UbuWeb, a concrete poem arranges language into a spatial ideogram on the page, making the typographic form fundamental to its meaning. In contrast, visual poems augment meaning with layout, but do not rely on shape to convey it.

Classic examples include:

• George Herbert’s Easter Wings, where the poem’s layout resembles wings, reinforcing spiritual ascent.

• Lewis Carroll’s The Mouse’s Tale, which curves down the page like a mouse’s tail.

Modern experimental works further expand the form:

• Dom Sylvester Houédard’s typewriter “artworks” use punctuation to create abstract patterns—like constellations or water ripples—where visual effect outweighs literal meaning.

• Russian futurist Tango with Cows uses printed wallpaper as the medium for poems, blending typography, materials, and radical layout.

⸻

Is There Space for Play in Poetry?

Certainly. Visual and concrete poems demonstrate that playfulness can coexist with depth. These forms allow language to become visual art, adding resonance and emotional punch. A “serious” poem might engage the mind; a concrete poem can simultaneously engage the eye, memory, and imagination. There’s profound potential in playful forms—even when they seem whimsical.

In your own creative process, where juxtaposing romantic images with absurd text is central, there’s synergy with the spirit of concrete poetry. You’re re-configuring expectations of poetry: breaking from linear, purely verbal form, and inviting playful visual disruption to generate meaning.

Visual Poem (shape adds resonance, but words stand alone)

The Lighthouse

steady

watchful

keeper of night

eyes of the harbor

holding sailors safe

guiding them to shore

with its pulse

of light

bright

star

steady

watchful

keeper of night

eyes of the harbor

holding sailors safe

guiding them to shore

with its pulse

of light

bright

star

Concrete Poem (shape = meaning)

Let’s take the word “wave”. Without the shape, it loses impact.

w a v e

w a v

w a

w

w a

w a v

w a v e

w a v e

w a v

w a

w

w a

w a v

w a v e

Sound poems

Rusty

The Voice of a Rusty Gat

crrrreee—eek

chk

chk chk

eeeeek—

(h-h-h-h-h)

crrk—snap

ee-eeeek

hush.

Reflection

- At first, it felt strange to avoid “real words.” But once I leaned into pure sound, it became almost musical.

- I realized the white space acts like pauses or echoes, like the way a gate swings in the wind and slows before groaning again.

- The poem feels alive because the object — normally mute — gains its own rhythm and personality.

Poem:

The Bridge at Dusk

We walked to the bridge

where the river whispered low:

scha-schhh, scha-schhh,

its silver breath weaving under planks.

The lamps flickered,

moths circling in whrrr-rrrp spirals,

tiny stars losing their way.

You laughed once,

a sound like glass:

clink—tink—plink!

then silence fell heavy as stone.

I wanted to speak,

but my tongue made only

mmm-hmmm, trrrrk, hhhhhh…

the language of the dusk,

half-music, half-confession.

Reflection

- Harder? Yes — because you need to balance sense and nonsense. Too much sound poetry, and the thread of meaning breaks; too little, and it feels ordinary.

- But the advantage is huge: you become more attentive to the texture of words, not just their dictionary meaning. Even in a normal poem, sound carries emotion (e.g., harsh consonants for tension, soft vowels for intimacy).

- Going forward, you might notice yourself “listening” to your lines as much as reading them, shaping rhythm and atmosphere more consciously.

Example 1: Found Poem from a

train station timetable

Arrivals, Departures

07:42 delayed

08:15 cancelled

09:02 on time—

change at Birmingham

platform numbers shifting,

please listen

for further announcements.

Example 2: Found Poem from a cooking recipe

The Boil

Add two cups of water,

wait until bubbles

rise like ghosts.

Stir clockwise,

then anticlockwise—

salt,

a handful of patience.

Reflection

- The timetable poem feels oddly existential — all about waiting, uncertainty, change. By simply breaking lines, it becomes more than functional language.

- The recipe poem becomes ritualistic — like instructions for a spell rather than dinner.

- Neither uses “my” words, but the act of shaping them still feels creative. It’s like finding patterns in noise.

- Personally, I’d say the timetable one feels like a “real poem” because it resonates with emotions (delay, waiting). The recipe one feels playful, but lighter.

Detachment? Maybe a bit — because the words aren’t originally mine. But the magic lies in noticing that poetry is often hiding in everyday texts. You’re not writing so much as revealing.

Research Task 7: Reflection on

“Deaf School”

by Ted Hughes and Antrobus’s Response

1. What do you think of the poem? Is it offensive? Why did Hughes write it?

Ted Hughes’s “Deaf School” describes deaf children using vivid, animalistic imagery—phrases like “small night lemurs caught in the flashlight” evoke a sense of exotic otherness, while “alert and simple” risks painting them as emotionally or intellectually limited .

While Hughes may have intended to depict the silent, intense mystery of deaf experience, the poem slips into a kind of detached observation that risks objectifying its subjects. It may not be overtly malicious, but from a modern, more sensitive perspective, it can feel presumptuous—using deafness as a metaphor for existential or linguistic ideas rather than engaging with the lived experience of deaf individuals .

Perhaps Hughes was exploring broader themes—the nature of language, silence, and alienation—but the lens of poetic abstraction doesn’t mitigate the fact that these are real people, not symbols. For those with lived experience of deafness, this can feel reductive or even alienating.

2. Why might Antrobus have blacked it out?

Raymond Antrobus, himself educated in a world where deafness was often misunderstood or misrepresented, saw in “Deaf School” more than poetic imaginings—he saw cultural insensitivity, reductiveness, and a mirror of historical marginalization .

By redacting the entire poem with thick black lines, Antrobus transforms the page into a visual statement. It’s cathartic, it’s jarring, and it’s transformative—a refusal to passively accept a flawed representation, and a way of visually asserting agency over the narrative .

3. Do you think he wanted people to look up the original?

Possibly—but I think that wasn’t the primary goal. Antrobus has shared that he initially wanted to strike through the text rather than fully redact it, to preserve visibility—but legal constraints pushed him to blackout the text entirely, which he found more powerful and “cathartic” .

In that sense, the blacked-out poem says more without words—it compels the reader to reckon with absence, erasure, and what’s missing, rather than encouraging a return to the original words. It invites reflection: what have we removed, why, and how do we respond? However, it’s a given that readers who are curious can still look up Hughes’s poem, opening the possibility of contrast and deeper engagement.

4. Is Antrobus’s poem really an act of censorship if an interested reader can easily find and read Hughes’s poem?

No—it doesn’t fit the dictionary definition of censorship, which suppresses access to a work. Instead, Antrobus’s blackout functions as a poetic critique and recontextualization. It’s an act of creative dissent, not institutional suppression.

The Poem: A Strange, Unsettling Lens

Reading Deaf School left me conflicted. Hughes is undeniably a poetic heavyweight, capable of powerful imagery and philosophical weight. But in this particular piece, something felt…off. The way he describes the deaf children — likening them to “small night lemurs caught in the flashlight” — is evocative, yes, but also deeply othering.

Hughes seems to be peering in from the outside, observing deafness as a kind of symbolic mystery. But these are not metaphors — they are people. Children. Real lives reduced to strange, almost exotic metaphors that risk dehumanizing the very subjects he’s attempting to portray.

There’s no malice in the poem, but there is a detachment. And from today’s lens — with greater awareness around disability, identity, and representation — it reads as outdated at best, and unintentionally offensive at worst.

Antrobus’s Blackout: More Than Erasure

Enter Raymond Antrobus — a Deaf poet whose work I’ve come to admire for its clarity, courage, and emotional intelligence. In his collection The Perseverance, Antrobus includes Hughes’ poem—but entirely blacked out. Just thick, inky lines where the words once were. It’s a visual punch. A moment of poetic interruption. A silencing of the “great” poet who, perhaps, had spoken over the very people he meant to write about.

Why did Antrobus do this?

To me, it’s more than a statement of offense. It’s an act of reclamation. A way of refusing to passively accept the canon’s authority. Antrobus doesn’t just critique Hughes — he takes control of the space. He transforms it into a silent, yet powerful conversation about who gets to speak and how we are seen.

He initially considered striking through the poem, but legal limitations forced a full blackout — which, interestingly, gave the piece even more power. It doesn’t scream. It doesn’t argue. It simply removes, leaving the reader to face the absence — and to wonder why.

Was It an Invitation? Or a Warning?

Some argue that by blacking out the text, Antrobus was cleverly inviting readers to look up the original — to confront it for themselves. I think that may be true, but I also think it’s beside the point.

The blackout is the poem now. It is the message. It’s not hiding the words out of fear; it’s confronting the damage they caused. It doesn’t stop people from finding Hughes’ version — but it forces a pause, a moment of reckoning before they do.

It’s not censorship. It’s critique through art. It’s what we as creatives often strive to do — to transform discomfort into dialogue.

Where This Lands With Me

This task made me think about representation, silence, and who holds the pen. As someone who writes from a place of deep emotional truth — shaped by displacement, difficult relationships, and the need for connection — I know how powerful language can be. But also how dangerous.

We don’t always get it right. Even great poets like Hughes didn’t. But what matters is the conversation that follows. Antrobus didn’t burn the poem. He responded with art.

And in doing so, he left a blacked-out page that somehow speaks louder than words.

Closing Thought

Art isn’t always about answers. Sometimes it’s about the echo — the space between voices. Deaf School, and Antrobus’s blackout, remind me that silence can be both violence and resistance — absence can be its own kind of presence.

As I continue my creative journey through the OCA and beyond, I carry this lesson with me:

Be careful how you look at others. Be even more careful how you speak for them.

Wriggling Like Houdini: Playing with Constraint and Form in Poetry

by Alex | Creative Arts Blog | Isle of Man, 2025

As part of my Creative Arts studies with the Open College of the Arts, I recently explored constraint-based writing — specifically through the playful and often surprising methods of the Oulipo movement and beyond.

Oulipo (Ouvroir de Littérature Potentielle), or “Workshop of Potential Literature,” challenges writers to work within very specific limits — not as punishment, but as a source of creative freedom. It’s like putting yourself in a poetic straitjacket, and then discovering that your limbs move in unexpected, brilliant ways.

Below, I share two poems written using different Oulipo constraints, followed by a third exercise: a poetic form I invented myself.

⸻

Oulipo Poem #1: N+7 Method

(Replace every noun in a text with the 7th noun following it in the dictionary)

Original Line:

The children sit in silence, hands folded in their laps.

N+7 Poem Version:

The chlorophyll signals in silkworm,

handcuffs foamed in their lawsuits.

Quiet as cold archives,

they loop like lanterns in the ladle of time.

✍️ Reflection:

This method was oddly liberating. The surreal images — “handcuffs foamed in their lawsuits” — are nonsensical on the surface, but they sparked strange connections and unexpected moods. It took me far outside my usual lyrical, emotional voice into something more abstract and experimental. Not a bad place to visit.

⸻

Oulipo Poem #2: Lipogram (No Letter “E”)

(Compose a poem that avoids the letter “e” entirely)

Poem: “A Room in Fall”

A dusk of gold, soft air

Holds still a world in shadow.

Winds pass, hush loud words.

A moth taps glass.

All is calm.

All is.

✍️ Reflection:

This was far harder than I expected. Avoiding “e” stripped my vocabulary bare, forcing me into minimalism. But that very restriction gave the poem a quiet, meditative tone — simple, but evocative. It taught me that sometimes fewer tools force greater focus.

⸻

Exercise 7: Creating My Own Form – The “Spiraline”

For this next task, I created my own poetic form. I wanted something short, focused, and expressive. A form that would expand line by line — like a thought spiraling outward.

🌀 Spiraline Form Rules:

• 5 lines

• Line 1 = 1 word

• Line 2 = 2 words

• Line 3 = 3 words

• Line 4 = 4 words

• Line 5 = 5 words (concluding or reflecting on the whole)

⸻

Poem #1: “After the Call”

Silence

follows always

after hard conversations

leaving nothing but fragments

and echoes of what was.

⸻

Poem #2: “Isle Sunset”

Gold

folds slow

into soft sea

sky blurs horizon’s ache

I watch without wanting answers.

⸻

✍️ Reflection:

Inventing this form was one of the most rewarding creative exercises I’ve done in a while. Its structure is tight, yet it opens beautifully into deeper emotional territory. It also gave me a helpful constraint without stifling my voice.

I named it the Spiraline because it mimics the spiral shape of growth and thought — starting from a single word and blooming into a five-word reflection. It’s deceptively simple and a great tool for focusing on the essence of an emotion or moment.

⸻

Final Thoughts

Constraint-based writing surprised me. It made me reconsider how form shapes content — not as a cage, but as a guide. These exercises took me far from my usual poetic comfort zone — yet they gave me new rhythms, new metaphors, and a fresh creative perspective.

As Will Eaves said in The Inevitable Gift Shop:

“Form will arise to express content.”

Whether it’s a blackout poem, a tritina, a questionnaire, or a five-line spiral, constraint can be a way in, not a wall keeping us out.

If you’re a poet stuck in a rut, try a lipogram. Try removing something vital. Try writing like you’ve never written before.

You might just find your voice all over again.