Exercise 2: Expanding Place

To expand on the context of the material you have collected from your walk, you will now investigate the wider aspects of place and how creative practitioners navigate ideas within their local environment. There is a deep-rooted historical context that underpins much of the activities and content within this project, meaning it is important to outline and research these before you continue.

Review the following resources document and the key text for this project, and collate notes and ideas in your learning log. Return to these resources as you move through the following activities to expand your awareness of the context of place and why you are being asked to consider this in more depth.

- Cresswell, T. (2015) Place an Introduction (2nd ed.) West Sussex: John Wiley & Sons Ltd.

- Introduction to Psychogeography

NOTES

“Psychogeography could set for itself the study of the precise laws and specific effects of the geographical environment, whether consciously organized or not, on the emotions and behaviour of individuals. The charmingly vague adjective psychogeographical can be applied to the findings arrived at by this type of investigation, their influence on human feelings, and more generally to any situation or conduct that seems to reflect the same spirit of discovery.”

Guy Debord, Les Lèvres Nues #6 (1955)

The dérive is a crucial method of psychogeographical enquiry. The literal translation from French is ‘drift’ and a dérive is a spontaneous, unplanned walk through a city, guided by the individual’s responses to the geography, architecture and ambience of its quarters. The flâneur (a term that originates from Charles Baudelaire and Walter Benjamin) is essentially the protagonist of the dérive, but more generally the ‘gentleman stroller’ (as Baudelaire put it) who enjoys the aesthetic pleasures of the sights and sounds he experiences. The flâneur has been identified in Edgar Allan Poe’s The Man of the Crowd (1840) and in the shady figure lurking in the corner of Edouard Manet’s A Bar at the Folies-Bergère.

SOURCES-MATERIAL

A stroll at the Loughborough city centre can generate a lot of inquiries and questions.

The dérive, the drift can be the beginning of a long and fruitful research about, the place, the story, and the people.

Being in the textile business for more than 30 years, it wouldn’t have been possible no to hear anything about a Loughborough local, William Cotton and his innovative spirit who played a significant role to the textile/knitting industry.

A statue, just in front of the town hall was the cause for a research about Bentley-Cotton knitting machines proudly made in Loughborough!

Loughborough Town Hall

Is the first building you get to see in the city centre.

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

| Loughborough Town Hall | |

|---|---|

| Loughborough Town Hall | |

| Location | Market Place, Loughborough |

| Coordinates |  52.77086°N 1.20638°WCoordinates: 52.77086°N 1.20638°WCoordinates:  52.77086°N 1.20638°W 52.77086°N 1.20638°W |

| Built | 1855 |

| Architect | William Slater |

| Architectural style(s) | Italianate style |

| Listed Building – Grade II | |

| Designated | 5 November 1984 |

| Reference no. | 1361164 |

The Loughborough Town Hall is a building fronting Market Place in Loughborough, Leicestershire, England. Built as a corn exchange and ballroom in 1855, it became a municipal building and subsequently a theatre. It is a Grade II listed building.

History

The origins of the building lay in the early 19th century when four Loughborough tradesmen began a movement to provide the town with a public gathering place. It received much more momentum with the involvement of the local MP, Charles Packe of Prestwold Hall, who donated £500 towards the enterprise. With his backing, other local gentry got on board, and £8,012 was raised to purchase land and construct the building.

The foundation stone for the new building was laid by Charles Packe in October 1854: it was designed by the Northampton-born architect William Slater in the Italianate style, built in ashlar stone and was completed in 1855. The design involved a symmetrical main frontage with nine bays facing onto the Market Place; the central section of three bays, which slightly projected forward, featured a round-headed doorway with a fanlight flanked by two rounded-headed sash windows separated by Doric order columns supporting an entablature and a balcony. On the first floor, there were round-headed sash windows separated by Ionic order columns supporting an entablature and a cornice. At the roof level, there was a two-stage decorative bell-cote.[1] The outer sections on both floors were also fenestrated by round-headed sash windows. The clock, which hangs from the main frontage of the building, was designed in 1879 and installed in 1880.[6] The bell, which was cast by John Taylor & Co, based in Loughborough was also installed at that time.

The primary uses in its earliest days were as a ground floor corn exchange hall, where local farmers could meet and trade. Upstairs was a ballroom for the use of the gentry. However, from the outset, all manner of public gatherings and entertainments were able to make use of the premises. Until 1888 Loughborough had no town charter and was administered by the lord of the manor, and more latterly by local boards with specific responsibility for water and sanitation works, highways, schools, and burials. When Loughborough received a charter in 1888, the new council took on these roles for the town and was in need of a suitably dignified administrative base. The Corn Exchange company agreed to sell the building and, after it had been converted into a town hall, it re-opened as a municipal building in 1890.

The suffragette, Emmeline Pankhurst, spoke at Loughborough Town Hall during the 1910 General Election.

The building was damaged during a serious fire in 1972. It was the headquarters of the Municipal Borough of Loughborough but it ceased to be the local seat of government when the Borough of Charnwood was formed in 1974. The building was converted into a theatre to the designs of Goodwin, Warner and Associates between 1973 and 1974. An extensive refurbishment of the building, which was undertaken by G. F. Tomlinson at a cost of £5 million, was completed in November 2004.

On 15 March 2023, a fire broke out in a branch of HSBC next to the town hall and spread to the roof of the building.

The Sockman

| The Sockman | |

|---|---|

| The Sock | |

| The Sockman in Loughborough Market Place. | |

| Artist | Shona Kinloch |

| Year | 1998 |

| Medium | Bronze sculpture |

| Dimensions | 185 cm × 130 cm × 60 cm (6 ft × 4 ft × 2 ft)[1] |

| Location | Loughborough, United Kingdom |

52.771069°N 1.206769°WCoordinates: 52.771069°N 1.206769°WCoordinates:  52.771069°N 1.206769°W 52.771069°N 1.206769°W | |

The Sockman (commissioned as The Sock) is a bronze statue in the Loughborough town centre.

The sculpture depicts a man seated on a bollard, naked except for the eponymous sock on his left foot.[2] The sock is symbolic of Loughborough’s hosiery industry, and the plinth is engraved with images of the town’s history.

The piece has become iconic and is used as a symbol for Loughborough.

History

In 1997, Charnwood Borough Council decided to have a sculpture to provide “an attractive feature and focus of the public interest” in the newly-pedestrianised Loughborough Market Place.[4] They chose a central site just in front of Loughborough Town Hall.

A competition was held in which five artists were selected to design a statue. A panel of local experts and laypeople were gathered to make the decision; the winning design was by Scottish sculptor, Shona Kinloch. Her piece was favoured for artistic quality, technical merit, and durability (being both weather and vandal-resistant).

My idea for the Loughborough Market Place is a man, rather on the stocky side, who sits admiring his zigzag sock. The design on the sock is inspired by the fact of the woollen industry, hosiery and knitwear being the speciality, contributing greatly to Loughborough’s prosperity.

He will sit on a bollard, which has been incised with images, in low reflect, from Loughborough’s history.

— Shona Kinloch

The council commissioned The Sock in April 1998 at a cost of £23,000.

The Sockman. (2023, January 4). In Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Sockman

The Hosiery Factory

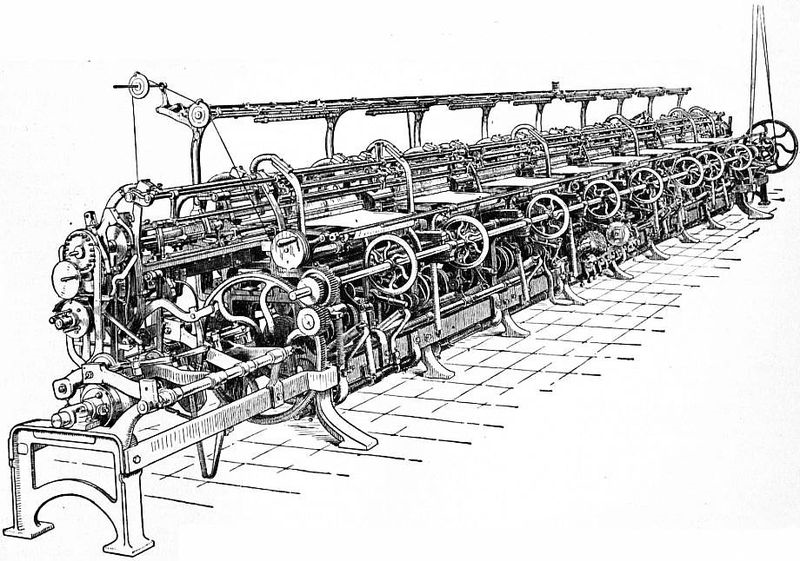

The manufacture of knitted goods was the last branch of the textile industry to adapt to mechanical power. Yarn spinning had been done by water power from the 1770s and by steam power from the earliest years of the nineteenth century but as the widespread use of steam-driven knitting frames did not develop until the later years of the nineteenth century, the industry never passed through a water powered phase.

Experiments with power-driven knitting frames were numerous during the nineteenth century. Marc Isambard Brunel was granted a patent in 1816 for a steam-powered circular machine, but the problems of the industry at this period presumably prevented its adoption. The idea of a circular machine was taken up again in the late 1830s since it could operate faster than a flat machine which involved a series of discontinuous movements. More circular machines were adopted after Matthew Townshend invented the latch needle in 1847. On this type of needle, the barb was operated by the yarn itself as the loops passed over it in a similar manner to a modern rug hook. The presser bar to close the needle beards were no longer necessary and so circular machines using latch needles were simpler to operate. Power-driven hosiery factories were opened in the middle decades of the nineteenth century but the machines could knit only circular fabric which was not shaped in any way and so it was used for cut-ups. Fashioned articles were still made on the hand frame and so inventors concentrated on the problem of widening and narrowing fabric automatically. Arthur Paget of Loughborough and Luke Barton of Hyson Green, Nottingham, both solved the problem of narrowing fabric in the same year, 1857, Paget producing a one-off machine and Barton a wide frame producing several lengths at once. Another Loughborough manufacturer, William Cotton, first solved the widening problem and then in 1864 received a patent for automatic narrowing and widening using a fine-gauge frame. His machine still made use of Lee’s spring bearded needles, but they were placed vertically in the frame and the sinkers horizontally, with the bar to which the sinkers were attached acting as a presser to close the needle beards. The apparatus for transferring loops to narrow and widen fabric hung above the row of needles and could be adjusted at the turn of a screw. Cotton’s machine was soon widely adopted in the hosiery trade and he established a separate factory which was producing a hundred machines a year by the late 1870s.

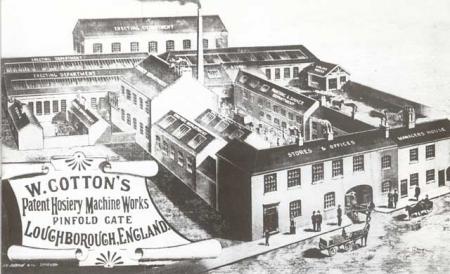

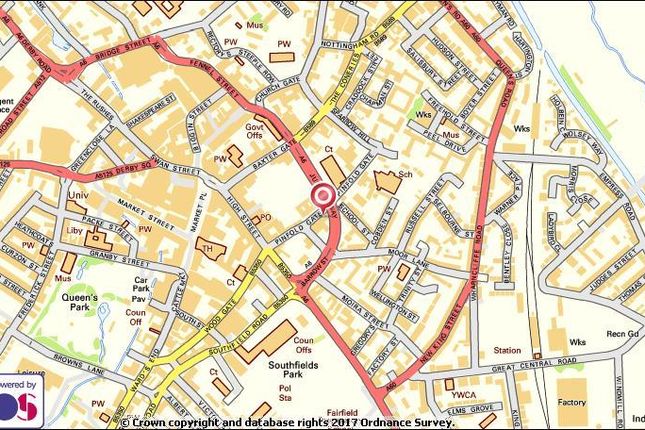

William Cotton invented the basic knitting machine movements used in modern equipment. He moved to this factory in Pinfold Gate, Loughborough, in the 1880s. The different buildings are identified in the engraving and include a forge, needle and sinker departments and several erecting shops.

He was born around 1819 and brought up in the village of Seagrave Lodge, near Leicester. He was apprenticed to merchant hosiers Cartwright and Warner of Loughborough, and shortly begin experimenting with a series of devices that eventually led to a powered knitting machine known as the ‘Cotton’s Patent’.

(William Cotton, Ltd., Loughborough.)

This machine introduced a number of changes to the knitting process undertaken on the old hand frame process, successfully transferring the hand and foot operations of the framework knitter to a machine that could be driven by rotary power from a steam engine. With steam power harnessed by Cotton’s machines, large-scale factory production of fully-fashioned garments was now possible in the knitting industry. Cotton himself opened a factory in Pinfold Gate, Loughborough in the 1870s and became one of the largest employers in the town.

Cotton died in 1887 leaving a company that continued to manufacture into the twentieth century. The versatility and quality of Cotton’s design ensured that Cotton left a legacy of machines working in factories across the world, with many early machines still in use after the Second World War, a working life of over eighty years.

Loughborough. (2023, April 3). In Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Loughborough

YEAR: 1921. From Leicester Chamber of Commerce Year Book.

The town of Loughborough’s name was engraved on the machine’s cover. These machines travelled to the most exotic places: USA, China, India, Australia, New Zealand, South Africa etc making Loughborough a place to visit to learn machine handling and troubleshooting from the experts who built them.

This clip is taken from the JOHN SMEDLEY website, the world’s oldest knitting factory, still using Cotton machines.

Peter Nightingale and his associate, John Smedley founded the company in 1784 at Lea Mills, Matlock, Derbyshire. Lea Bridge provided an ideal setting for the mill, as the brook that ran through the village provided motive power and a constant source of running water.

(source: the JOHN SMEDLEY) official website.

EAW044578 ENGLAND (1952). The William Cotton Ltd Knitting Machine Factory on Pinfold Gate and environs, Loughborough, 1952. This image was marked by Aerofilms Ltd for photo editing.

Map of Pinfold gate as it is now.

People are creating history by shaping their environment, by designing objects of great spirit in it and if sometimes their name is forgotten in the sands of time, their impact stands strong as their innovations have shaped the world we are living in today.